...at the end, Garder [the last Norse settlement in Greenland] was like an overcrowded lifeboat… famine and associated disease would have caused a breakdown of respect for authority… starving people would have poured into Gardar… slaughtering the last cattle and sheet… eating the dogs and newborn livestock…

Jared Diamond, Collapse

So writes Jared Diamond on the end of the Norse (Viking) settlement in Greenland, evoking the visceral terror of crazed and desperate Vikings on the rampage for whatever raw meat they could lay their hands on. The trouble is – as Gordon Campbell points out in his recent book Norse America (see my review here), and as others have pointed out before him – there is no evidence for this. In fact it is just as likely they sailed back to Norway and lived happily ever after.

To be fair to Diamond (who is one of my favourite authors) he does precede this passage by saying “I can’t resist fleshing out [sic] the end with some speculation“.

But even so others of his more sober supporting arguments now look to be proven incorrect – for example carbon in sediments appears to be evidence of manure on the fields rather than Vikings burning precious trees to clear land.

Collapse was and still is one of the best popular history books I have read. But for the 15 years since I read the book I have had the wrong idea about the Norse in Greenland.

Does it matter?

Does it matter if history is wrong in general?

There are of course different ways to be wrong. Here are three:

- You can be deliberately misleading

- You can misinterpret information and then be shown to be incorrect

- You can make a conclusion on insufficient information and later turn out to be incorrect (when more info is available)

- You could have no information and just make something up that seems plausible

- If we caught someone doing the first of these we wouldn’t think much of them. But in fact in terms of impact they are all equivalent: we end up believing something which is untrue.

But whatever the cause of the error I would argue that the error is unimportant.

It doesn’t matter.

If history is wrong that’s fine

This is because – if we assume that we are reading history to extend our knowledge or experience – even incorrect histories help to build a framework of knowledge, or scaffolding for our thoughts. As we read more we can adjust the framework or hang extra things off it. But without a framework it is very difficult to retain any information at all in our heads.

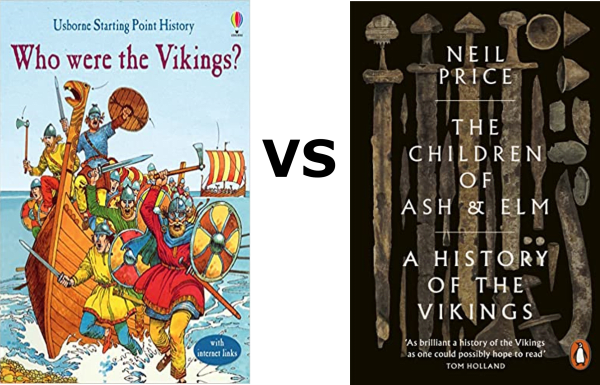

Which one is righter?

For example, when I was an undergraduate studying modern history, we would be given reading lists at the beginning of a term, packed full of learned and often very dense text, usually on an area of history of which we had no previous knowledge. I discovered it was much easier to read and enjoy these academic books if first I went to the library and got out a kids book on the same subject. It might have been full of dubious generalisations and out of date opinions (and fun pictures), but when I went back to the “serious” book I had a context in which to place it and I could absorb it much more easily – and rebuild and replace the framework created by the kids book.

Caveat lector

There are a couple of caveats that I should make to this claim.

-

Firstly incorrect history books don’t matter only if we are as readers always reading with an open (but also sceptical) mind, and ready to cut out the mental deadwood that we inevitably build up.

-

Secondly there are extreme cases where incorrect history books definitely do matter: where they lead to violence or other sorts of harm.

So we must accept responsibility as a reader to read critically.

Paradoxically: as long as we care about history being right, it doesn’t matter if it is wrong.

Going back to the example of Diamond’s book Collapse: before I read this book I had no idea that Norse settlers lived in Greenland for 500 years. I also had no idea about the other peoples who lived in this part of North America – the Dorset peoples or Thule Inuit. My understanding of what happened was incorrect but I was given the context in which to appreciate other stories about this period. Our horizons can be wider even if the view is dubious!

But there can be a related problem with history writing which I think is much worse: selectivity.

A fate worse than being wrong

If we only read and write about a narrow set of topics, ie we are too selective, we will have historical blind spots that can be much more damaging. Back to Greenland: if we only read about the Vikings we might skim over the more important and more relevant experience of the 50 million native American peoples who were there for thousands of years before Europeans.

I’m British and the historical myopia we collectively suffer from is in my view an obsession with World War 2. This 6 year period (for the British) accounts for easily more than 50% of all history books sold in the UK (source: guesstimate). But by just reading about this one event we miss a wider perspective that allows us to understand our ourselves better, or other people from other countries.

So it doesn’t matter if history is mistaken, but it does matter if history is myopic.

Going back to Collapse by Jared Diamond: I would still encourage everyone to read this book, but read it critically, and don’t make my mistake of only reading this book, read other books too!

While on the subject, don’t trust me either (why would you?). You might think I’m wrong about being wrong. If you do, then set me right with a comment.