The Greek Historian Herodotus reports that the Egyptians carried a painted corpse made of wood inside a coffin into their drinking parties. The host then displayed the corpse to each of the guests in turn, saying. “Look at this as you drink and enjoy yourself. You’ll be like that when you die.”

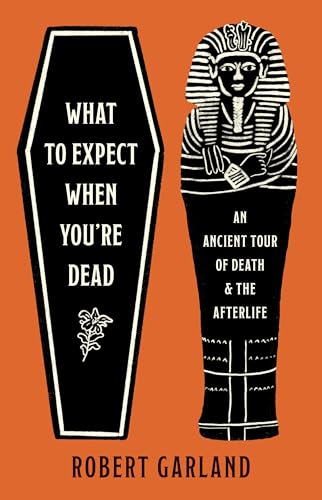

Robert Garland, What to Expect When You're Dead

In fact, stories told by Herodotus make a frequent appearance in the book. He appears to have enjoyed a death-related anecdote – we also get the two brothers who died dragging their mum to a festival in an ox-cart (the oxen didn’t turn up in time) which apparently was a great way to die and made them the second most fortunate men to have ever lived;1 and a Persian tribe called the Massagetae who killed, stewed, and ate their elderly when they got too old (described as “the most blessed way to die”).

What’s in (and not in) the book?

The book focuses on ancient Western and Near/Middle Eastern religions: Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Hindu, Jewish, Zoroastrian, Etruscan, Greek, Roman, Early Christian, and Islamic. The book also covers the evidence of the earliest beliefs and practices among Mesolithic and Neolithic communities. So, we get a broad chronological and geographic spectrum, from the fossil remains of 28 hominins found in a deposit called Sima de los Huesos (”Pit of Bones”) in north-central Spain dating from approximately 430,000 BC to Islamic funerary rituals laid out in fiqh literature, the earliest parts of which date to the eight century AD.

The author notes the belief systems not covered, which include most of those prevalent in East Asia (Confucian, Shinto, Buddhist) and pre-Conquest America (Aztec, Mayan).

A macabre smorgasbord

Having said that, the author enjoys drawing liberally from any and all analogies where he thinks it is interesting or entertaining to do so, including frequent references to what we do and do not do today with our dead.

At no point does the book attempt to justify or explain its own scope (either geographic or temporal). The author’s PhD thesis was turned into his first book ‘The Greek Way of Death’, so I expect he has just drawn on the topics he knows most about. The overall effect is a miscellany of amusing and entertaining anecdotes; this is the type of book you might want to buy someone as a fun birthday or Christmas present.

That is not to disparage the author’s erudition in any way – the book is a treasure trove of fascinating information, and I’m sure the author has published plenty of dry academic tomes in his day, but this book is clearly trying to achieve something slightly different.

What is the book like to read?

The book opens with the line ‘Studies prove that everybody dies eventually’ and a similarly dry/sardonic tone is prevalent throughout. Coupled with the author’s own overt scepticism and atheism, you get the impression that Professor Garland would enjoy sharing a drink with Chrisopher Hitchens (when he was alive) or Richard Dawkins whilst chuckling to themselves over the absurdities of human behaviour and beliefs.

At one point the author queries whether we can ‘seriously think that ancient people believed that the food that lay mouldering beside the tomb contained nutritional value for the dead’. Many will consider that a reasonable question to ask. But if that sounds like the type of thing that is likely to irritate and/or offend you, you may be advised to steer clear.

Is there anything I didn’t like about the book?

I had the feeling throughout that I would have got more out of the book had the author structured it chronologically or around specific religions. The structure chosen maximises the amusement/anecdotal qualities of the book, but I was left struggling to put together a coherent picture of what different religions thought about death, how those compared to one another, and how different ideas about death interacted with one another over time.

Ideas for dying well

The book was certainly thought-provoking. As I grow older and face my own inevitable doom, it inspired a number of observations about how to meet my end:

-

Die rich and/or powerful: the author points out that death was class conscious and what we know about it mostly concerns powerful men. The Egyptian belief in life after death appears to have started with the Pharaohs and then gradually worked its way down the social ladder over the millennia. What did slaves think happened to them when they died?

-

Avoid powerful enemies: if proper treatment of the dead was a preoccupation of ancient civilisations, then desecration of the dead was a great way to intimidate your enemies: for example, Assyrian King Sennacherib boasted that he “cut the throat of his enemies like lambs … made the contents of their gullets and entrails run down upon the wide earth … cut their testicles off and tore out their privates like the seeds of cucumbers” etc. etc. (you get the impression). I’ll never look at a cucumber in the same way again.

-

Move to Egypt: (or somewhere else which is very dry): the Egyptians were especially obsessed with death and devoted enormous economic resources to it.2 The author speculates whether this could be because the desert preserved bodies particularly well (and raises the irony that mummification just replicated what the desert did, but less effectively).3

-

Don’t count on immortality: where does the belief in life after death come from? The author argues that pre-historic humans would have almost always died prematurely which might have resulted in an assumption that a person could go on living indefinitely, provided they avoided being eaten by something bigger. I wasn’t entirely convinced by this argument – presumably some people did, occasionally, die of old age and someone would have noticed that?

-

Plan your last words: the Emperor Claudius, whose last words were reputedly “I think I’ve shat myself” should have been better prepared.

-

Likewise, think about a nice epitaph for your tomb: the Romans seem to have demonstrated a little more originality in this respect than is common today4 – Tiberius Claudius Secundus observed that “Baths, wine, and women bring about life’s decline. Yet what is life without baths, wine, and women”.

-

Ask your relatives/neighbours not to eat you (unless you’re into that kind of thing and/or it’s culturally appropriate).5

-

Avoid dying young in ancient Rome (I’ve already achieved that), where it was forbidden by law to mourn the death of a child under the age of three (for a child under the age of six, parents were restricted to one month of mourning).

-

Avoid being pronounced dead before you die (or actively engineer it, depending on your proclivities). There is the obvious risk that you might be buried/cremated alive. However, even if you avoided that fate, if you were found to be alive after being pronounced dead the likelihood is that you would have been treated with a great deal of suspicion and subjected to strange rituals – in ancient Greece, for example, you would be wrapped in swaddling bands and breast-fed, to symbolise your re-birth.

How far we’ve come

The author concludes his book with some wry observations about the current state of belief in the afterlife: he notes that 7 out of 10 Americans believe in the afterlife (a proportion that has been largely constant since the 1960s),6 including 20% of agnostics and 13% of atheists.7 Given the amount undertakers get away with charging, of which I have some unfortunate recent experience, we still put a great deal of weight on making sure that the dead are properly taken care of.

Conclusion

This is a fun read and an excellent source of anecdotes to bring out at the next party you attend. In fact, why not bring a wooden corpse with you and really liven things up?

Number one was an Athenian called Tellus, who was survived by his children and grandchildren, died fighting for Athens, and was given a public funeral. ↩︎

The author notes that the pharaohs spent more resources on constructing pyramids than on their temples, or anything else (the Great Pyramid was the tallest building on earth before the Industrial age) and has an interesting observation about how such monumentality reflects on the highly centralised and authoritarian nature of power in ancient Egypt. ↩︎

We are informed elsewhere in the book that mummification remains available today – a company called Summum offers the service for $67,000. If that sounds expensive, consider the plight of the Athenian Diogeiton, who was expected to spend 5,000 drachmas on his brother’s tomb (enough to feed a family of four at subsistence levels for five to seven years). ↩︎

Although I like the tomb in Highgate Cemetery which has the one-word inscription “DEAD”. ↩︎

The author cites the interesting story of Persian King Darius who tried to pay the Greeks to eat their dead and the Kallatiai not to eat their dead (each contrary to their respective customs). Each refused, regardless of the amount of money offered. Personally, I think I could be convinced. ↩︎

Based on a study by Cornell University in 2011. ↩︎

Based on a Pew poll taken in 2013. ↩︎

Book details

(back to top)- Title -

What to Expect When You're Dead : An Ancient Tour of Death and the Afterlife

- Author -

Robert Garland

- Publication date -

April 2025

- Publisher -

Princeton University Press

- Pages -

344

- ISBN 13 -

9780691266176

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -