Back in 2001 Maddox Von Ranke and I were in a small Moroccan mountain village, planning an ascent of Mount Toubkal.

Mount Toubkal is the highest mountain in North Africa (I believe) and we had everything we needed packed into our oversized rucksacks: tent, food, cooking stove, sleeping bags, clothes.

However, as experienced walkers, we knew we were missing one crucial item: a map of the route.1

But curiously everyone we asked seemed surprised that we wanted one. A map seemed to be viewed as a rather eccentric request.

After a few hours we gave up. There is a happy ending though because as we sighed into our glasses of freshly squeezed orange juice our luck turned. The cafe owner, hearing of our plight, had photocopied a page from an old book containing a map of the route up Mount Toubkal.

When he handed it over to us we were delighted and we resolved to buy all of our freshly squeezed orange juices from his cafe from that point on.

The map was clearly drawn for tourist illustration rather than orienteering - the sort of map that Bilbo Baggins might have drawn to show how to get to the Lonely Mountain and back again - but it gave us confidence and we set off the next morning with a spring in our step.

You can interpret this tale in two ways:

-

A culture clash between fundamentally opposed European and North African world-views - with the map representing European notions of self-consciously heroic and individualistic endeavour.

-

A couple of rather naive youngsters who should have realised that if you are at the foot of the highest mountain in North Africa and you want to climb the highest mountain in North Africa you just need to keep going up.

Sara Caputo in Tracks on the Ocean: A History of Trailblazing, Maps and Maritime Travel investigates the origin and development of the idea of showing ocean tracks on maps, asking similar questions of what they might tell us about (Western) society and culture, albeit with rather more consequential anecdotes than my self-indulgent one above.

Where did oceanic tracks come from?

The book starts with the observation that tracks on the sea - marking where a boat has been or could go - are a surprisingly modern phenomenon, with the first clearly identifiable track appearing “almost out of nowhere” to show voyages such as Ferdinand Magellan’s who sailed around the world with a small fleet of ships from 1519 to 1522, although Magellan himself didn’t make it back.

They also seem to be a European idea, correlating with Spanish, Portuguese, British and French voyages of exploration and colonisation. Other cultures had maps of course, but examples of sea maps seem to be vanishingly rare.

So what is so special about showing the route of a ship on a map, and why did the idea take so long to catch on?

Because ship tracks, unlike land routes, are artificial constructs. The foamy wake left behind by a vessel can only become a solid line if one adopts a specific cartographical mindset. The fact that pre-modern people privileged other ways of reporting navigation shows that this mindset is not universal.

Sara Caputo, Tracks on the Ocean

Alternative mapping options

To put this in perspective, the clearest example of a non-European map showing a ship’s track was a map showing the voyage of the Ming dynasty Chinese Fleet of eunuch Admiral Zheng He who explored as far as the East African coast between 1405 and 1433.

A page from the Mao Kun map showing some of Admiral Zheng He’s voyages (source Wikipedia)

But even this map used a fundamentally different way of representing the world, with the scale representing the number of days travel rather than distance and the drawings of the land seemingly there mainly for decorative purposes.

So what do we make of this?

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the world suddenly stretched under Europeans’ feet... Maps were recruited in understanding and apportioning this novel immense space... The world was a theatre to human action... But now it was also something that humans made, and ruled from above.

Sara Caputo, Tracks on the Ocean

Is it real?

Central to the idea of the book is that “All maps ‘lie’ and fabricate, by approximation, addition, omission, distortion, or in a myriad other inventive or accidental ways.”

Or to put it another way, a map is a representation of reality not reality itself (which would be inconvenient to carry around). Therefore choices have to be made about what to show and not to show. These choices will reveal the attitudes and preoccupations of the map makers, which are typically more than just helping people get from A to B.

Incredible journeys

Caputo uses the track of Francis Drake and his voyage around the world as an interesting example of this ‘map distortion’ effect. After Drake had returned back to England in 1580 a number of maps were published showing the route that he took. The funny thing is though, that these maps were all rubbish. Caputo tells us that they would be useless for anyone looking to repeat the voyage, and looking at the map of Francis Drake’s circumnavigation on wikipedia, I agree with her.

Detail from map contemporary map showing Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the world (source Wikipedia)

The purpose of these maps then, is not navigational but propagandistic and political.

Up to the present

Her later chapters bring us up to the modern day with ocean going tracks morphing into surveillance tools - which can be used as nefarious tools of control, but equally can be used to detect and prevent bad actors getting away with misdeeds (such as surreptitiously dumping shipping oil in the sea).

Man overboard

I found Caputo’s perspective on the world as revealed by ocean tracks to be always thought provoking and sometimes fascinating.

However I couldn’t get fully onboard with all of her ideas. Perhaps the main issue was that I am less of a relativist.

While I agree that all maps are to some degree subjective, they would have no power (subjective or otherwise) if they didn’t meaningfully represent the real world. If the track of Francis Drake’s voyage showed him going via the North pole to the Pacific Ocean, that track line has no impact because it is not credible. Even though South America is drawn like the splat of a badly fried egg, it is still ‘true’ that Drake went round the bottom of it.

Uncertainty principle

In a similar vein, a fair bit of the book covers how maps showing a ship’s tracks on the sea can’t really be trusted because the navigators themselves were often not 100% certain where they were. (Plus measurements are taken periodically whereas tracks are usually drawn as unbroken lines.) I wasn’t all that impressed by this observation because every measurement anyone ever takes anywhere has some error margin, but the measurement is still useful if the error margin is small enough for the scale you are interested in.

Culturally or technologically contingent?

The other theme of the book that I wasn’t sure about is the idea that tracks are intrinsically European cultural artefacts, representing their desire to control the world and blaze a heroic personal trail across the oceans. So when Caputo says “If Western tracks had started like East Asian ones - as anonymous networks of sea paths - none of this would have happened”2 I’m not really convinced.

This is a bit of a chicken and egg question: Europeans were the first to draw lines on the ocean. But was this because of their intrinsically individualistic Europeanness, or because they just happened to be the bit of humanity who first figured out how to girdle the globe?

This is my personal bias but I think that if any group of people had found themselves capable and incentivised to rampage around the world, maps and tracks would follow.3

What is it like to read?

While I didn’t agree with all of the arguments in the book I loved reading it. Caputo writes in flowing prose that is easy to read. She invites the reader into each chapter with carefully chosen stories. She conveys a passion and fascination for the sea and maps that is infectious.

There are also lots of pictures of maps and charts throughout the book, as you might expect, and lots of colourful plates in the middle.

I would say it is an almost brilliant book - the only thing holding it back is that (in my view) there is no compelling argument running through the book other than “don’t trust maps”.

Conclusion

Born of imperial arrogance, solidified through colonial technology, and manifested through environmental pollution: both precarious and violent, tracks embody many of the contradictions inherent to modern mobility.

Sara Caputo, Tracks on the Ocean

Whether or not you are a map buff, whether or not you like ships, and whether or not you agree with the quote above, Tracks on the Ocean provides a fascinating take on global history of the last few hundred years.

For completeness: we were also concerned that we hadn’t brought a compass and spent a fruitless afternoon searching Marakesh for somewhere to buy one. To this day I still remember how to say compass in French (boussole.) ↩︎

I should admit that I don’t know exactly what ‘this’ is here, but I think it is the competitive instinct to boldly go where no man has gone before, and generally leaving havoc and destruction in their wake. ↩︎

Just to be clear, I'm not saying “it’s fine to behave badly, everyone is doing it”. For example I still tell my kids off even though I expect them - like other kids - to behave badly from time to time! ↩︎

Book details

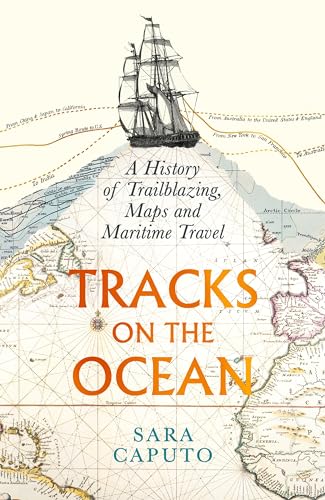

(back to top)- Title -

Tracks on the Ocean : A History of Trailblazing, Maps and Maritime Travel

- Author -

Sara Caputo

- Publication date -

August 2024

- Publisher -

Profile Books

- Pages -

320

- ISBN 13 -

9781788168823

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -