This is a fascinating description of what happened to certain Anglo-Saxon (and Anglo-Danish) individuals and families in the years immediately following the Norman Conquest. But as the author herself says, 'This book will explore not only what happened to some members of this generation of children but also, just as importantly, the ways in which their stories were recorded, retold and remembered – or forgotten'. In doing so, the book can be enjoyed in different ways.

On one hand, it follows individual narratives which, due to the drastic changes of fortune recounted, are naturally dramatic and enjoyable to read.

But equally, the book is an interesting study of how a culture reacts when it had been violently disrupted – the complex interplay of conflict, accommodation, and adaptation, is a recurring theme of the book.

The way Anglo-Saxon England was remembered (and forgotten) in the post-conquest years can tell us a lot about how England chose to remember its pre-Conquest history.

What the book covers

The book is made up of five chapters, with each focusing on a particular individual or family, but usually also with a wider lens on the various people they were connected to and interacted with:

- Chapter 1: Hereward, who was later mythologised as fighting a guerilla campaign of resistance to the Normans in the Fens around Ely.

- Chapter 2: Margaret of Scotland, daughter of Edward of Exile, born in Hungary, brought up in England, and then fleeing to Scotland post-Conquest, eventually marrying the King of Scotland and posthumously venerated as a saint. Her daughter Edith would go onto marry Henry I and therefore reunite the House of Wessex1 with the new Norman kings.

- Chapter 3: the grandchildren of Gytha and Godwine, including the children of King Harold.

- Chapter 4: Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria, the only 'martyr' of the Conquest, who was executed in 1076 for rebellion against William I.

- Chapter 5: Eadmer of Canterbury, a monk at Canterbury who tried to preserve the traditions of Anglo-Saxon Christianity.

Wipeout

In the introduction, the author notes that 'At the highest level of society, the Normans effectively wiped out the English elite, systematically dispossessing them of their lands: by the time of the Domesday Book in 1086, according to the estimation of Hugh Thomas, only around 6 per cent of the land in England was in English hands.' This book focuses on a handful of individuals and families who were prominent in pre-Conquest England, who were most directly impacted by the Conquest and whose stories have survived.

Hereward the Wake

The book starts with perhaps the most romanticised of the post-Conquest stories of Anglo-Saxon resistance, that of Hereward, an English nobleman, forced to flee England (pre-Conquest) for bad behaviour, who then enjoyed (we are told) adventures in Ireland, Cornwall and Flanders, returning to England on hearing of the Norman conquest to reclaim his birthright and fight the French. The extent to which any of this is true is, of course, open to doubt. But Ms. Parker speculates that his myth may have been passed down by local oral storytelling which preserved these traditions. What is interesting is that one of the most romanticised of the retellings of his story comes from Anglo-Norman verse written in the early twelfth century for French patrons, Gaimar's Estoire des Engleis, perhaps indicating the speed with which cultural cross hybridisation worked on the new Norman elite (albeit that this version of Hereward's story also involved Hereward accepting William as his king and settling back down into quiet retirement, so it also had a happy (Norman-friendly) ending).

In the chapter on Hereward, the author is particularly good at evoking the landscape of the medieval Fenland, forgotten to us today as a result of extensive drainage schemes in the seventeenth century. Much of the romance of Hereward's stories comes from that landscape and the hero's supposed familiarity with it: a local freedom fighter waging warfare on home turf/water-logged bog against an invading enemy.

The House of Wessex

With the second chapter, we move to the descendants of Alfred the Great: Edward the Exile and his family. Edward the Exile was the son of Edward Ironside, whose death in 1016 left Cnut in control of England. Edward the Exile ended up in Hungary, and his three children, Edgar, Margaret, and Cristina were likely born there. Edward and his children then moved back to England 1057, perhaps on the request of Edward the Confessor who may have been looking for a successor. Edward the Exile promptly died after his return (which apparently nobody at the time thought was suspicious) but his three young children were thereafter raised in England. For obvious reasons, their family was one of those most immediately impacted following the Battle of Hastings – Edgar Ætheling was elected as King of England but never crowned, and in 1068 the family fled to Scotland, where Margaret married Malcolm III of Scotland in 1070. Margaret's daughter Edith then went on to marry Henry I in 1100 (Norman noblemen would refer to them scathingly as 'Godric and Godiva' behind their backs). It was Edith (by this point renamed Matilda to make herself more palatable to the Normas) who did much to memorialise her mother Margaret, who would come to be regarded as a saint. Edith commissioned Turgot, prior of Durham, to write Margaret's biography. Turgot was the same age as Margaret and knew her well, as he tells us in his biography. That biography glosses over a lot of the disruption and conflict arising from the Norman conquest, which you would expect from a biography commissioned by the wife (albeit Anglo-Saxon) of a Norman king.

Edward the Exile's other children enjoyed a much less famous posthumous reputation. Cristina entered Romsey Abbey and was entrusted with the education of Margeret's daughters Edith and Mary. She apparently covered Edith's head with a hood to protect her from randy Frenchmen, which Edith objected to. Edgar seems to have floated in and out of the new Norman elite's orbit, at one time living in Normandy and being close friends of Robert Curthose, eldest son of William of Conqueror, but eventually sailing off to fight in the first crusade. He was largely ignored or dismissed by post-Conquest authors, except surviving interest shown in some versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, who perhaps still saw him as a last remaining hope for a return of Anglo-Saxon rule. For Norman writers, they felt themselves on safer ground with Margaret rather than with the surviving male heir to the House of Wessex.

The rise and fall of the House of Godwine

With the next two chapters, we move into a different world of the Anglo-Danish elite which established themselves during the reign of Cnut. The meteoric rise and fall of the House of Godwine would make for a great television series. Godwine, the son of a Sussex thegn, acquired a position of enormous power and wealth during the reign of King Cnut, marrying the King's Danish born relative Gytha. Following Godwine's death, we are told that 'at the beginning of 1066, Gytha was still a formidable presence, holding estates which made her one the wealthiest women in England. At the start of that year, her surviving children dominated the highest positions in English politics: her daughter was Edward's2 queen and three of her sons held earldoms. The day after Edward's death on 5 January 1066, her son Harold was crowned King of England. By the end of that year, all this was gone.' Gytha lost four of her six sons within three weeks: Tostig at Stamford Bridge, then Harold, Gyrth and Leofwine at Hastings. Gytha and her remaining sons may have been involved in rebellions in the South-East of England in the aftermath of the Battle of Hastings. Following a siege of Exeter in 1068, one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that 'And here Gytha, Harold's mother, travelled out of Flat Holm3, and the wives of many good men with her, and stayed there for a time, and from there went across the sea to St Omer'.

Much of our knowledge of the Godwine's grandchildren comes from Scandinavian rather than English sources. Of note is Gytha of Wessex (Harold's daughter). In the aftermath of the Battle of Hastings, she and two of her brothers fled to the Danish court (which they were related to through her grandmother's family). She eventually married Vladimir II Monomakh, becoming a princess of Kievan Rus. Through that marriage, she is the ancestor of many European royal families, including the British.

The Godwinsons were largely ignored by English sources (both Norman and Anglo-Saxon) post conquest. The pre-eminent family of pre-Conquest England largely disappear from the sources, with only Scandinavian sources taking any interest. For the Anglo-Saxons, the ancestors of Alfred the Great appear to have been of more interest; for the Normans, Harold was an oath-breaker and imposter who they were happy to forget.

Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria

In Chapter 4, we meet Waltheof, Earl of Northumbria, the last of the Anglo-Saxon earls after the Conquest, who was eventually executed by William I for supposedly supporting a rebellion against him. Clearly, for some, that execution (the only one of an English nobleman by William I) was highly controversial, and fed an enduring interest in Waltheof's story.

Waltheof was another product of the Cnut era Anglo-Danish elite. His father was Siward, a Dane closely connected with Cnut's reign. Waltheof seems to have closely identified with his Danish heritage, as the main source we have for him is an Old Norse poem composed in his honour by a skald named Thorkell Skallason. Thorkell was possibly part of Waltheof's retinue and may have been specifically employed by Waltheof as a skald. As the author notes 'skaldic verse of this kind belongs to a specific strand of masculine, military, elite Scandinavian culture' and indicates a lot about Waltheof's sense of identity and cultural affiliation.

Waltheof's daughter Maud went on to marry a Norman nobleman, Simon de Senlis, who was granted the earldoms of Northampton and Huntingdon, probably through right of his wife. After Simon's death, Maud married David of Scotland (son of Margaret and Malcolm) who also received the earldom of Huntingdon and landholdings in the East Midlands. Both David's and Simon's descendants (in the case of the former, Kings of Scotland) would claim an interest in what became known as 'the honour of Huntingdon', through their descent from Maud.

Eadmer of Canterbury

In the final chapter, we are presented with a different aspect of the Norman conquest – its impact on English Christianity, through the figure of Eadmer of Canterbury. A child oblate brought up in the community of Christ Church, he later wrote about his memories of the pre-Conquest Church. Those memories were particularly relevant after the cathedral was destroyed by fire in 1067, an event that acquired obvious resonance for those who witnessed it. Eadmer's descriptions of the old Cathedral were remarkably detailed, with its physical layout providing a map of 500 years of Christianity in England. Eadmer and others like him did much to preserve the memories and traditions of Anglo-Saxon Christianity in the period after 1066.

What is it like to read?

This was an easy and entertaining read. It is only 201 pages long (excluding notes and bibliography) and, as already mentioned, is naturally engaging, recounting stories of individuals who faced dramatic circumstances and reacted to those in different ways.

Except for Eadmer of Canterbury, everyone covered in this book was aristocratic; most were powerful and rich. This not surprising – the landowning elite were those most immediately and directly affected by the Conquest. Also, as is always the way, they were the ones most written about. The book draws exclusively on written sources, rather than archaeology. None of this is a criticism – the author is open from the outset on the scope and subject matter of her book, but it is useful to be aware of.

Those written sources are themselves extremely limited. As a result, much of the book is taken up with speculation and extrapolation from that very limited material. The author is a Professor of English literature, so textual analysis clearly comes naturally to her. We are told about how someone's name may have been chosen in memory of some other person; how stories draw upon different narrative traditions; how a person may or may not have been present at a particular battle. If you are looking for hard facts about what happened when, you may end up disappointed. But the author is skilful at conveying the relevance of not only what may or may not have happened, but how events and people were later remembered, misremembered, or forgotten.

Conclusion

By focusing on particular individuals and families, the author succeeds in drawing out some of the pathos and drama of a pivotal moment in English history.

Those individuals and families are not necessarily representative of the experience of the English as a whole – for much of the peasantry life before and after the Conquest might not have seemed all that different – but those stories are not only of inherent interest but illustrate the broader cultural changes that would feed into a new Anglo-Norman England.

By the House of Wessex, I mean the Anglo-Saxon kings of Wessex and their descendants, including Alfred the Great. A little confusingly, Godwin (father of King Harold) was made the first Earl of Wessex by King Cnut in around 1020, which is why Harold's daughter Gytha is sometimes referred to as 'Gytha of Wessex'. ↩︎

The Confessor. ↩︎

The author notes that this is a small island in the Bristol Channel, not much more than an outcrop of rock. ↩︎

Book details

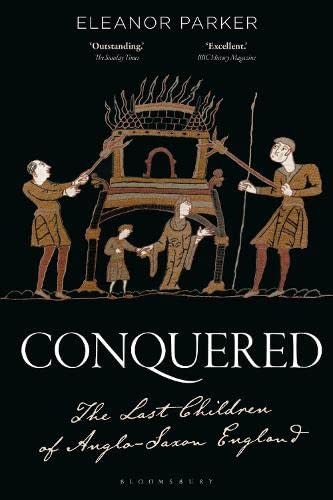

(back to top)- Title -

Conquered : The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England

- Author -

Eleanor Parker

- Publication date -

February 2022

- Publisher -

Bloomsbury Academic

- Pages -

272

- ISBN 13 -

9781788314503

- Podcast episode -

- Podcast episode -

Gone Medieval: 1066 What Became Of The Anglo-Saxon Children?

- Amazon UK -

- Amazon US -